MEDIA LITERACY IN EUROPE: 12 GOOD PRACTICES THAT WILL INSPIRE YOU

ABOUT THE EVENS FOUNDATION

The Evens Foundation initiates, develops and supports projects that encourage citizens and states to live together harmoniously in a peaceful Europe. It promotes respect for diversity, both individual and collective, and seeks to uphold physical, psychological and ethical integrity. The Evens Foundation is a public benefit foundation based in Antwerp, Belgium and with offices in Paris and Warsaw. The Foundation initiates and supports sustainable projects, and awards biennial prizes, that contribute to the progress and strengthening of Europe based on cultural and social diversity, in the fields of media, peace education and European citizenship.

INCREASING MEDIA LITERACY IN EUROPE BY HIGHLIGHTING GOOD PRACTICES AND FOSTERING LIVELY EXCHANGE

Since 2009 the Evens Foundation has been striving to increase media literacy in Europe. It has initiated and supported numerous media educational projects, collaborated with many organizations from all over Europe, and facilitated networking and learning opportunities for them. The Foundation also awards a biennial Evens Prize for Media Education. A wide variety of excellent projects being run all over Europe have applied for this.

After almost five years of work in this field, reading about hundreds of projects that seek to increase media literacy in Europe, visiting dozens of them and getting directly inspired by their energetic work and dedication, we decided it was time to create a platform for a selection of these practices. We wanted to share what we had discovered so that more people would be inspired by the great work of these projects, learn from them, and even integrate some elements in their own work.

To give this publication a solid basis, it was necessary to do some additional research, making sure the projects meet certain criteria, collecting extra information about them, editing the presentations, etc. To help realize this project, the Evens Foundation cooperated with JFF – Institute for Media Research and Media Education, the laureate of the Evens Prize for Media Education in 2011.

From 2012 onwards we worked intensively on this publication. To enlarge our knowledge we set up an advisory board composed of experts in media literacy from different European countries: Dag Asbjørnsen, policy officer of the European Commission (Norway), Evelyne Bevort, delegated director of Clemi (France), Kathrin Demmler, head of the JFF – Institute for Media Research and Media Education (Germany), Ike Picone, research professor at the Department of Communication Sciences of the Free University of Brussels (Belgium), Ida Pöttinger, president of the Association for Media Education in Germany (GMK) (Germany) and Patrick Verniers, president of the Master’s in Media Literacy at IHECS (Brussels journalism and communication school) (Belgium). The Evens Foundation warmly thanks all members of this group for their generous commitment to this project, their valuable advice, and the insights they shared with us.

This advisory board not only helped us with the final selection of the 12 projects; members also wrote a personal recommendation for each, explaining why it was chosen and what is remarkable about it. The projects in the publication did, of course, have to comply with certain criteria: to use media and teach media literacy, and be innovative, sustainable and transferable. We ensured a good geographical spread, and selected just one project from any particular country. We sought to show that there are good projects run in schools as well as in non-school contexts, for all kinds of target groups, and with different kinds of media. We don’t claim that these are the best practices in Europe, but they are all good practices; all have their own particular merits and deserve to be highlighted.

As we grew familiar with the projects and the people involved, these projects began to take a place in our hearts. We also felt vindicated in the belief that it is important to present the variety of good ideas and projects in Europe for teaching media literacy. So we hope that, with this publication, we are passing on great ideas on how to increase media literacy, and also initiating an intensive exchange between those who are engaged in this field all over Europe.

IN THIS ISSUE

- MEDIA LITERACY IN EUROPE

- LEARNING WITH ASSASSIN’S CREED NORWAY

- CAT CYPRUS

- THE ECONOMY OF THE MEDIA ITALY

- STREET SCHOOL FRANCE

- MEDIASIS ROMANIA

- NATIONAL MEDIACOACH TRAINING PROGRAM THE NETHERLANDS

- POLSKA.DOC POLAND

- A JOURNEY IN A WONDROUS WORLD BELGIUM

- ELECTRIC DECEMBER UNITED KINGDOM

- MEDIA VOICES 4 SPECIAL TEENS SERBIA

- GENERATIONS IN DIALOGUE GERMANY

- THE VIDEOMUSEUMS GREECE

- GLOSSARY

- BIOGRAPHIES

- COLOPHON

MEDIA LITERACY IN EUROPE

MEDIA ARE OMNIPRESENT IN OUR EVERYDAY LIVES. FAMILY LIFE IS SO SATURATED WITH IT THAT EVEN VERY YOUNG CHILDREN ARE CONFRONTED WITH A PLETHORA OF MEDIA IMPULSES ON A DAILY BASIS. CHILDREN WATCH TV OR THEY LISTEN TO MUSIC OR STORIES ON CD, BUT, BECAUSE OF THE WIDESPREAD ADOPTION OF TECHNOLOGIES SUCH AS THE INTERNET AND MOBILE DEVICES, THEY ALSO SEE THEIR PARENTS HANDLING MEDIA IN MANY DIFFERENT SITUATIONS.

Our global society is moving from a literary to a digital society. Media, especially digital, have an extraordinary impact on society’s formative processes; they have an enormous influence on our beliefs and even behavior. For these reasons, all fields of pedagogical work need to engage with media. Media literacy must therefore be discussed as one of the key competences that young people need to learn. All over Europe, many organizations are dealing with media literacy, while the European Commission has shown strong recognition of its importance: “The way we use media is changing and the volume of information we get today is enormous. People need the ability to access, analyze and evaluate images, sounds and texts on a daily basis, especially if they are to use traditional and new media to communicate and create media content. Consequently, the European Commission considers media literacy an extremely important factor for active citizenship in to- day’s information society. Just as literacy was at the beginning of the twentieth century, media literacy is a key prerequisite of the twenty-first century.”

The European Commission, assisted by an expert group of European media literacy experts, has developed a definition of media literacy as broad knowledge in the daily use of media. More specifically, it defines media literacy as the ability to:

- Access the media

- Understand the media and have a critical approach toward media content

- Create communication in a variety of contexts (http://ec.europa.eu/culture/media/ media-literacy/index_en.htm)

Media literacy is ubiquitous and therefore a necessary part of lifelong learning. However, the main focus of media educators all over Europe is still on children and adolescents. With reference to the Commission’s definition, the promotion of media literacy has to deal with four main challenges:

- Ability to access the media: Children and adolescents must be able to use media in their daily life, according to their needs. This includes the technical part of having media in classrooms, in places of ‘open youth work 1 ’ and at home. Although we often call the young generation ‘digital natives’, it is wrong to assume that all young people automatically have access to fast Internet and the newest media devices. Being able to use media also includes knowledge on how to find answers to different questions. Especially in dealing with specific media and media applications, young people often know more than adults and can take over independent tasks in educational processes. We have to keep in view that technical access should be guaranteed for everybody, while also developing overall competence in dealing with information and maintaining a pedagogical perspective.

- Understanding the media: Young people have to be informed about how media systems work in their country, in Europe and worldwide. They also need to deal with issues such as maintaining a media/ life balance, the connection between media and economics, and between media and violence, and so on. The media/violence correlation is particularly acute when it comes to computer games. For many young people, playing computer games is an important leisure activity. They spend a lot of their spare time playing. But there seems to be a clash of two worlds: on the one hand, young people are fascinated by computer games; on the other, society holds a rather negative view about these new media forms. The challenge is to teach the young gameplayers to be critical users, but at the same time to help outsiders to understand youngsters’ fascination with these games and consequently that computer games can also be a tool for learning. To counteract a clash of generations, we have to support communication between children and their parents, children and teachers, and children and politicians. In this dialogue all involved parties can voice their point of view and learn much about the other generation and about media and media use. Teachers have to be aware of the meaning of media and reflect upon their own role. They are no longer just the ones who ‘have the information’; they also need to know how to moderate the processes of learning.

- Adopting a critical approach to media content: Young people mainly use online media to stay informed, but they have to learn to distinguish between trustworthy and untrustworthy information, and to pay attention to the sources. Especially with social networks and user-generated content, this is becoming increasingly crucial. In all educational contexts, critical selection of content, the need to form one’s own opinion, and debate on questions such as copyright and privacy are very important. A critical approach to media content also implies taking into consideration the combination of media content and advertisement. Early on, children are confronted with many kinds of advertisement. They are surrounded and directly targeted by media protagonists (e.g. SpongeBob & Princess Lillifee) representing a worldwide merchandising system. They are also confronted with advertisements in films, in computer games, on the Internet and even in apps for children. Many young people have never been taught the economic aspects of media. The process of developing the media literacy of children and adolescents must embrace these issues so as to help them acquire the knowledge and skills to be able to use media critically and distinguish valuable media content from other content, such as advertisements, especially when indirect or disguised.

- Creating communications in a variety of contexts: Media are very important for young people to stay in contact and to communicate with their peers, and using media is the most effective way of influencing opinion or even behavior in society. Young people have to learn how to use media to respectfully express their opinion and how to involve others in public discussion of important topics – in other words, how to ethically use media to participate in society. Therefore, they have to know how media information is produced, how to create their own media content, and what channels they can use to take part in public communications – either in their neighborhood, in their society at large or even in worldwide discussion. Promoting media literacy includes supporting young people in creating their own media content and making available channels for the distribution of media content. There are radio and TV channels for young people in many countries, but it is a new challenge to find the right, trustworthy way to publish content online. Teachers have to decide whether to use commercial options or to create safe spaces for pedagogical work. Taking into consideration the phenomenon of mediatization and the development of the ‘social web’ and mobile media, the question is no longer: Does education need to deal with media? The question is rather: Do educators perceive the potential of media use, or do they simply dismiss the media as problematic and dangerous? Following the definition of media literacy, the answer is obvious: It must be the goal of media education to take the interests of adolescents in media seriously and to help them to express their interests and viewpoints by using media. Activities concerned with media must have a wide focus and give the young people many options to engage and participate. Young people, with their particular interests and cultural and social backgrounds, should be central to media literacy education. In the educational process they should be taught how to handle media and how to use them as a means of communication. To promote media literacy, we need examples of good practice as well as teachers who understand the media and the issues involved, and who are open to the interests of young people. Therefore, media educators must take recent developments into consideration and assess their significance for their own concepts and actions. All processes concerned with the promotion of media literacy must reflect both media and socio-political developments, reflect on them critically, and draft, test, evaluate and publish innovative practical concepts, which can then serve as models. We are convinced that the following 12 projects will serve as models for inspiration and that many will follow their fine example.

“The way we use media is changing and the volume of information we get today is enormous. People need the ability to access, analyze and evaluate images, sounds and texts on a daily basis, especially if they are to use traditional and new media to communicate and create media content.”

LEARNING WITH ASSASSIN’S CREED A GAME-BASED HISTORY CLASS

THIS PROJECT IS BASED ON AN ORIGINAL YET VERY CONVINCING AND WELL-DESCRIBED PEDAGOGICAL IDEA. IT IS FOUNDED ON A CRITICAL STUDY OF HISTORICAL DEPICTION IN A COMMERCIAL VIDEO GAME, BUT IT SHOULD BE FAIRLY EASY TO ADAPT TO OTHER MEDIA TEXTS AND SETTINGS. THE PROJECT TEACHES THE STUDENTS MEDIA-SPECIFIC SKILLS RELATED TO VIDEO GAMES AND COLLABORATIVE WORK USING SHARED DOCUMENTS (BASED ON GOOGLE DRIVE). IT TEACHES SKILLS THAT ARE ESSENTIAL TO MEDIA LITERACY: UNDERSTANDING HOW HISTORICAL MATERIAL IS USED IN A COMMERCIAL PRODUCT, AND HOW TO ASSESS THE ACCURACY OF INFORMATION FOUND IN A TEXT. IT ALSO HAS A CREATIVE ELEMENT, AS THE RESULT IS A SHARED PRODUCT, AND SHOULD BE HIGHLY ENGAGING FOR THE STUDENTS. (DAG ASBJØRNSEN)

NFORMATION ABOUT THE ORGANIZATION THAT RUNS THE PROJECT

INITIATOR Magnus H. Sandberg, teacher at Stovner videregående skole, Oslo: Magnus Sandberg developed a manual for educational use of the game Minecraft in school for the Norwegian Media Council (http://dataspilliskolen. no/upload/2013/02/28/250113_ minecraft_undervisningsopplegg_ web.pdf)

CONTACT PERSON Magnus H. Sandberg

CONTACT mhsandberg@gmail.com

WEBSITE http://about.me/magnussandberg

PROJECT SUMMARY

The students explored a commercial video- game that was made for entertainment but had a realistic historical setting. By questioning what they saw, heard and were made to do in the game, and by researching their own questions using online sources, they constructed their own curriculum about the historic period and subject.

AIMS: With the help of a computer game the students learn about the history of the chosen epoch. They reflect on where our historical assumptions come from and on how the purpose of telling a story can affect how it is told. They find out how academic thinking can relate to modern pop cultural expressions. Furthermore, they learn to communicate in writing and construct knowledge collaboratively.

TARGET GROUP(S): Students in public schools. This game franchise is best suited to upper secondary school/high school (rated PEGI 15 or 18). However, given the nature of this particular game, it can be discussed “... a very clever history class. It was motivating, fun, and we whether these age limitations should apply. In any case, the same design of a study process can be used with other story-based game titles.

MEDIA: computer game, Google Drive, Internet, library (optional)

METHODS: constructivist learning, through curiosity about the game and carrying out independent research online (and/or in books), formulating questions and researching them, communicating in writing online

DURATION OF THE PROJECT: at least three hours, preferably a whole school day

RESOURCES NEEDED: 2 teachers; the students work in groups of four to six; every group needs PS3 or similar gaming console, the game, PCs with Internet connection, Google Drive

DESCRIPTION OF THE PROJECT

Video games are a fairly new medium. They are interesting as a medium for storytelling, but increasing attention is also being given to games as a tool for learning. Some games are developed as tools for learning (often termed serious games), but this project is an attempt at organizing learning activities with games that are made for entertainment.

Many games have a theme or a setting for the story that makes it interesting to research the relation between the game and the real world. The games in the Assassin’s Creed franchise are set in different historic settings. The first game is set during the Crusades in the 12th century; the three following games are set in 15th (see video presentation of the use of the game in a history lesson: http://www.youtube.com/ watch?v=_w38NdfT4_8&feature=youtu.be) and 16th century Italy and Constantinople. The most recent game is set in 18th century North America, before and during the American Revolution.

The games are well suited for learning history, but require that the player be sensitized to the game’s ‘fruitfulness’ while skeptical about using an entertainment product as a source for factual knowledge. We achieved this by splitting the students into groups with clearly defined roles. One group should play the game and pose questions about the historic depiction. The other should research those questions and come up with answers. The two groups worked in different rooms and communicated by writing online in a Google document. They asked and discussed questions concerning historical facts and information but the validity of the information in the game. The digital cooperation and communication were essential to avoid the project being just a fun day of gaming at school.

“... a very clever history class. It was motivating, fun, and we actually learned a lot, even though we did not think about that [what we were learning] along the way”

METHOD(S)

This project is not designed according to any specific method that we knew of beforehand, but the project is about collaboratively generating research questions, and answering them in the context of the game-story.

An issue that is strongly accentuated in the design is the question of learning in context vs. learning out of context. History classes can easily be about memorizing things only because the teacher says it is important. In the context of the game, everything the students research has a purpose – namely, to make sense of and increase understanding of the game-story.

ADDITIONAL DESCRIPTION OF ONE DAY OR PART OF THE PROJECT

Split the class into groups (four to six students) and each group into two subgroups (two to three students). One subgroup needs a gaming console connected to a TV/projector, and a PC (laptop). The other subgroup needs to be in a separate room with a PC per person (e.g. stationary PCs in a computer lab).

While one subgroup is playing the game, they disuss what history-relevant questions can be posed concerning the people, surroundings and story in the game. Their job is not to find answers, only to come up with questions. They write down their questions in a Google document (Google Drive) and share this with the other subgroup.

It’s the job of the other subgroup (in the different room) to research the questions that the first subgroup poses. They might have to ask for more details and context for the questions. The information they find should relate in a meaningful way to the context in the game.

The subgroups should switch places at least three times, so they experience both roles and have an opportunity to change the performance of their role after getting insight into the other role. Those in the playing group should also change places among themselves, so that everyone gets to experience each role.

It’s important that both groups are aware of their responsibility to keep the other group busy. This is strongly motivating. They should also have in mind that the outcome is the document that results from both individual efforts and the good communication within the group and between the two groups.

We will finish this section with an example of how the two subgroups collaborate to explore the history of Assassin’s Creed 3:

Early in the game the player character arrives by ship in Boston. Almost immediately he meets Benjamin Franklin who needs help to collect pages of his almanac that have been swept away by the wind. The player subgroup write about this in the shared doc and ask the research subgroup to find out who Franklin is.

The research subgroup find a lot of facts about Franklin and add some of them to the document. They also ask the player group how they got to know about Franklin, i.e. what kind of info is relevant. When they hear about Boston and the almanac, they have some clues as to what info is relevant in the game context.

The final text in the document will hopefully retell the in-game narrative and then discuss to what degree it is historically accurate. It cannot be written by one student alone, and the two groups have to collaborate.

This early scene in the game has cues for a great number of other research questions. Other historic figures (General Lee and Thomas Hickey), different professions, ships and cargo in Boston Harbor, city life in Boston, military uniforms and weapons, etc.

WHAT YOU SHOULD PAY SPECIAL ATTENTION TO

Make sure the part of the game (the save game) is ready to be played where it is relevant for the class. For example, Assassin’s Creed starts with a frame narrative set in contemporary times. That part is not interesting for a history class.

Make sure both groups work in the Google document. The teacher and all the students have a Google account. The teacher starts a ‘new document’ and shares it with the members of the group. Then the teacher can see in real time how the group works with it, and make sure everyone contributes. The teacher can also access a document history to see what contributions have been made by whom. Consult the Google Drive help section for more details on this.

Remind both groups that it is their responsibility to keep the other group active by giving them new tasks.

WHAT DIFFICULTIES WERE ENCOUNTERED IN IMPLEMENTING THE PROJECT?

The challenges are mostly technical. It is important that the teacher has already tested that all the equipment works. Since most schools don’t have gaming consoles, pupils need to bring their own. They should do this no later than the day before, and everything should be checked to make sure it works. Usually the school will need to provide the game in as many copies as needed.

WHAT COULD BE IMPROVED

Things should work well if the procedure described here is carefully followed. There have been moments when something did not work (e.g. the connections between the console and the school projectors), and the class had to begin with setting up the equipment. This can take up a lot of time, so it is highly recommended to check every thing well before the class begins.

CAT

CYPRUS ARTEFACT TREASURE IN ACTION

THE CAT PROJECT ENABLES CROSS-CURRICULAR COMMUNICATION AND PROMOTES PEACE EDUCATION AND MEDIA EDUCATION THROUGH DISCUSSION AND DOCUMENTING OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL HERITAGE. IN THIS WAY IT COMBINES REALLY INTERESTING TOPICS AND AIMS. IT IS AN OUTSTANDING INITIATIVE IN A DIVIDED COUNTRY AND MAY BE A GOOD EXAMPLE FOR MANY OTHER COUNTRIES OR REGIONS, TO PROMOTE MEDIA LITERACY AND TOLERANCE. WITH ITS CLEARLY DEFINED MEDIA EDUCATIONAL AIMS, IT IS EASY TO COPY AND ADAPTABLE TO DIFFERENT SITUATIONS. IN THE PROJECTS, YOUNG PEOPLE USE MEDIA TO EXPRESS THEMSELVES AND TAKE ALL STEPS IN THE PROJECT. THEY DISCUSS THEIR CULTURE AND THE HISTORY OF THEIR COUNTRY IN GROUPS FROM BOTH PARTS OF CYPRUS; PLAN A STORY AND REALIZE IT WITH VIDEO, MOSTLY WITH STOP-MOTION, AND FINALLY PRESENT THEIR VIDEO.

THE CAT PROJECT HELPS CHILDREN TO USE MEDIA TO CROSS FRONTIERS, TO EXPRESS THEMSELVES AND TO BUILD FRIENDSHIPS. MEDIA ARE USED IN TWO WAYS. ON THE ONE HAND THE CAT PROJECT RESPONDS TO THE FASCINATION WITH MEDIA PRODUCTS (MOVIES, YOUTUBE CLIPS OR OTHER WEB CONTENT) OF YOUNG PEOPLE ALL OVER CYPRUS; ON THE OTHER HAND IT ENABLES YOUNG PEOPLE TO CREATE COMMUNICATIONS IN A VARIETY OF CONTEXTS. COM- BINING HISTORICAL ASPECTS AND NEW MEDIA IS A GOOD AND MODEL WAY FOR MEDIA EDUCATION IN DIFFERENT PEDAGOGIC FIELDS. (KATHRIN DEMMLER)

INFORMATION ABOUT THE ORGANIZATION THAT RUNS THE PROJECT

Since 2005, the International Children’s Film Festival of Cyprus (ICFFCY), a Greek Cypriot non-profit association, has been organizing the festival for all children in Cyprus. It’s the only festival of its kind on the island to combine movies with education, and it therefore builds strong links with all the schools and different communities involved. Cinema and its role in the lives of young people is the focus of this annual event, and the films selected use educational criteria, which are aimed at enabling the children to become active citizens in today’s world.

ICFFCY also implements various media education projects (since 2009). It is a founder member of the CCMC (www.icffcy.org).

INITIATOR: Bérangère Blondeau, Media Educa- tion teacher, ICFFCY board member

PARTNER(S): Magusa Kültür Derneği (Famagusta Cultural Association); Antamosis; Cyprus Community Media Centre (CCMC); Master 2 AIGEME Sorbonne Nouvelle Uni- versity

CONTACT PERSON: Bérangère Blondeau

CONTACT: berangere.blondeau@icffcy.net bblondeau@hotmail.com

WEBSITE: www.icffcy-cat.com

PROJECT SUMMARY

The Cyprus Artefact Treasure in action – CAT is a media education project intended for Greek and Turkish Cypriot communities as well as international communities of the island, focusing on Cypriot archaeological artefacts.

The CAT project enables cross-curricular communication and promotes peace by implementing media education through the lens of archaeological heritage. The children and adults had the opportunity to interact and create different media products illustrating and bringing alive their common culture, building long-lasting friendships and true dialogue between communities. The CAT project promotes strategies for conflict resolution, intercultural dia- logue, and respect for human rights.

AIMS: to enable cross-cultural communication, and promote respect for human rights and conflict resolution by implementing media education through the lens of archeological heritage. Culture is promoted as a field for reconciliation, peacebuilding and intercultural dialogue.

TARGET GROUP(S): 20 children, 10/11 years old, from two different groups, and 10 teachers (five from each group) in a conflict or postconflict zone

MEDIA: various – video, radio, photography, film, mobile phone, etc

METHODS: project-based teaching and crosscurricular work promoting educational innovation, which place the children and pre-adolescents in the center of the learning process, allowing the construction of participatory knowledge

DURATION OF THE PROJECT: from 3 to 12 months, with a meeting every month/month and a half

RESOURCES NEEDED: 10 teachers (five from each community), language facilitators, media-makers, media equipment, animation box, stationery

DESCRIPTION OF THE PROJECT

Cyprus, the third largest Mediterranean island after Sicily and Sardinia, is located at the extreme east of the sea. Since 1974 the country has been divided into two parts: the southern part, the Republic of Cyprus, recognized by the international community, where the Greek Cypriot community lives, and the northern part, the ‘Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus’ (TRNC), proclaimed in 1983, recognized only by Turkey, where the Turkish Cypriot community and a large number of Turkish nationals live. Between the two parts a line known as the ‘green line’ or ‘buffer zone’ is occupied by the United Nations Force in charge of peacekeeping in Cyprus (UNFICYP).

The CAT project was developed to promote strategies for conflict resolution, intercultural dialogue, and respect for human rights through working with media on the common cultural heritage of both parts of Cyprus. It was carried out in partnership with the Master AIGEME (1) of La Sorbonne Nouvelle University and the CCMC-Cyprus Community Media Centre, and was funded by the Bicommunal Support Program (BSP) of the American Embassy in Cyprus. The project was implemented by ICFFCY, a Greek Cypriot association, in cooperation with two associations, Magusa Kültür Derneği (Famagusta Cultural Center) in the Turkish Cypriot community and the cultural organization Antamosis in the Greek Cypriot community. The CAT project was implemented for two years, from October 2010 to December 2012. During the first year CAT 1 focused on cultural heritage from the period 650-500 BC (archaic Cyprus): the Ayia Irini col-lection. CAT 2 in the second year worked on Cypriot medieval artefacts.

The joint work and discussions about ar-chaeological objects have created dialogue between communities, and thus initiated the establishment of long-lasting and sus-tainable links among participants.

The CAT project was built on three levels which in their own way established and emphasized three of seven media education competencies (2): Citizenship, Crosscultural Communication and Conflict Resolution.

- The first level, run in part-nership with the Association for Historical Dialogue and Research (AHDR) gathered a group of professors (archaeologists) from both communities who have examined the archaeological collection and imagined, created and published two educational documents in three languages: Greek, Turkish and English. These pedagogical documents allow teachers to work in Cyprus on Cypriot archaeological objects, promoting the establishment of a process of intercultural dialogue, historical multiperspectivity and critical thinking.

- The second level of implementation of the CAT project brought together 20 children from two opposite parts of the island: 10 children from the Greek Cypriot community of Paphos, and 10 children from the Turkish Cypriot community of Famagusta. The children, aged 10-11, chose an archaeological artefact on which they wanted to work. In bi-communal groups they created media products featuring their objects – short animation films, radio programs, video clips of a drama production, photos, etc.

- The final part of the CAT project was implemented in the media education classes of the American Academy Nicosia, a private English-speaking school. The school welcomes Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots but also a very international population. The students have produced various media products highlighting the different artefacts, including ‘art books’ illustrating the Ayia Irini collection, diaries, and blogs presenting medieval Cyprus.

The CAT project helps children to use media to cross frontiers, to express themselves and to build friendships.

METHOD(S)

The CAT project is a cross-curricular media education project illustrating a specific Cypriot archaeological collection. Team work in the planning, evaluation and follow-up at all levels of the project is essential and compulsory, as constant dialogue and true listening initiate reconciliation and peacebuilding practices. The participants, who learn new practices and use media devices (camera, animation box, sound and video editing), work together and are engaged in a creative and participatory knowledge process, allowing them to develop a media product illustrating Cypriot culture. The project method enhanced self-confidence, provided a positive and safe environment for meeting the other community, and enabled the free, happy exchange and acquisition of personal skills. It also involved active collaboration that resulted in a special feeling of being a member of and establishing the CAT community.

ADDITIONAL DESCRIPTION OF ONE DAY OR PART OF THE PROJECT

THE WONDERFUL ADVENTURE OF CAT 1, THE BICOMMUNAL GROUP

CAT 1 was attended the first year by 20 children from two opposite parts of the island: 10 from the Greek Cypriot community in Paphos, a town in the far west of the island, and 10 from the Turkish Cypriot community in Famagusta. These children spoke either Greek or Turkish only. Ability in English was sporadic. Aged 10-11, they were enrolled in state schools, in their last year of primary. In the Turkish Cypriot community, the CAT project was implemented with an association of teachers that organizes social and cultural activities for young people and families, Magusa Kültür Derneği (Famagusta Cultural Association). In the Greek Cypriot community, the project was supported by the local cultural association, Antamosis.

The objectives of the CAT project were the discovery of archaeological artefacts, in particular those of the Ayia Irini collection, and the creation of small bicommunal animation films illustrating this collection. The adventure started in October and in November 2010 with two workshop sessions in the communities themselves.

Gradually friendships developed and habits were taken as small routines that rooted these two groups into a single entity, with its own culture and habits

- October 2010: workshop in partnership with a media-maker in each community (in Paphos and in Famagusta) regarding animation film and the different film techniques (different shots, angles and their meaning, the functioning of a cam-era, tripod and basic filming techniques)

- November: workshop in a museum to discover a Cypriot archaeological collection: visit, choice and adoption of an artefact in the collection (for the Paphos community, a visit to the National Archaeological Museum in Nicosia and, for the Famagusta community, a visit to the Morfou Museum)

- January, February 2011: four common workshops in Nicosia at the Cyprus Community Media Centre (CCMC) located in the buffer zone. Each group of children came by bus from their home town. The children, in bicommunal groups and with the help of teachers and language facilitators, wrote a story illustrating their artefacts, drew up a storyboard and shot their animation film following the storyboard they had developed. They decided and created in bicommunal groups all the scenery of their film, designed the various archaeological objects, characters and sets, and created the music and sound effects as well as the poster of their film.

During these joint meetings children and adults got to know each other, to talk and to share moments: food, games, group work. Gradually friendships developed and habits were taken as small routines that rooted these two groups into a single entity, with its own culture and habits.

Whenever they met, the same procedure was followed, which created a dynamic interaction between individuals. Each child had to find a person of the other community and give him/her the right name tag. The children were very fast in memorizing all the names, whereas the adults had more trouble. Each session ended with an evaluation of the day, recorded in a small diary. The children wrote about their feelings, what they had liked or not, and what they had discovered. All this enabled them to realize what they had learned during the day and introduced them to the slow process of discovering each other and changing their picture of the other community.

The bicommunal meeting, at which children in a mixed group had to give birth to the story of their film, was a challenge. There were almost as many language facilitators as children! The pedagogical knowledge of the teachers of both communities was amazing. They supported the children in their discussions, often using – in addition to translating the various conversations from one language to another – body language, mimes or drawings. It was a challenge to produce a short and simple story out of the joint work between the Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot children.

Five short films were made and presented to the public at the closing ceremony of the annual International Children’s Film Festival of Cyprus (ICFFCY) in February 2011.

In the following year the CAT 2 project was implemented at the request of the bicom-munal group. This time the media products illustrated medieval Cypriot artefacts.

WHAT YOU SHOULD PAY SPECIAL ATTENTION TO

A) The collaboration between ICFFCY and Famagusta Cultural Association and Antamosis has been very positive; the project benefited from the different connections, manpower and legal status of each association.

B) The general organization was again supported through strong collaboration between the two associations, allowing parents of the CAT participants to send their children across the border, which demanded trust of the people and, specifically, of the organizers.

C) To assist communication, translators and mediators from both communities were provided.

D) Buses were paid for to go to the different parts of the island and to visit the archaeological sites and collections.

E) Lunches, snacks, drinks and resources were provided by the project.

F) The CCMC partnership allowed the CAT team to use the media equipment and benefit from media-makers as well as the CCMC facilities (conference room, outdoor space and toilets)

WHAT DIFFICULTIES WERE ENCOUNTERED IN IMPLEMENTING THE PROJECT?

In the CAT bicommunal group:

A) Communication when organizing the meetings, as text messages were not possible across ‘the divide’, although some practical solutions were found and tried: Facebook account, Dropbox, a Greek Cypriot number for the Turkish Cypriot leaders, etc

B) No press releases and no press coverage in either community, due to lack of manpower in this area

C) Distance between the two communities: Paphos (south-west of the island) and Famagusta (North-east)

D) Language and communica-tion issues; children from Paphos speaking Greek and children from Famagusta speaking Turkish

WHAT COULD BE IMPROVED

It would be very helpful to have a communications officer to dis-seminate and promote the CAT project in Cyprus and outside of Cyprus. The achievement in conflict resolution that resulted in the CAT bicommunal group, especially in the context of the Cyprus problem, could

(1) AIGEME: applications informatiques: gestion, education aux médias, eformation.

(2) According to Divina FrauMeigs media education is based on seven skills: understanding, critical thinking, creativity, consumption, citizenship, crosscultural communication and conflict resolution (Frau-Meigs, D., Socialisation des jeunes et éducation aux médias. Du bon usage des contenus et comportements à risque. Toulouse: Érès 2011.

THE ECONOMY OF THE MEDIA

MANY MEDIA LITERACY PROJECTS THAT FOCUS ON CHILDREN AND SOCIAL MEDIA MAINLY PAY ATTENTION TO ASPECTS OF PRIVACY, CYBER-BULLYING, ETC. CENTRO ZAFFIRIA, HOWEVER, ADOPTS A UNIQUE APPROACH TO RAISE CHILDREN’S AWARENESS OF SOCIAL MEDIA DANGERS; ONE WE BELIEVE CAN INSPIRE OTHER INITIATIVES. IT’S REMARKABLE THAT MEDIA LITERACY IS NOT ONLY THE AIM OF THE CENTER’S PROJECTS, BUT ALSO THE METHOD THROUGH WHICH CHILDREN ARE INVITED TO THINK ABOUT OTHER ASPECTS OF SOCIETY, SUCH AS THE ECONOMY. UNDERSTANDING THAT YOU ‘PAY’ FACEBOOK WITH YOUR LIKES NOT ONLY TEACHES YOU TO BE CAREFUL ONLINE, BUT ALSO GIVES YOU A GOOD SENSE OF FUNDAMENTAL ECONOMIC PRINCIPLES AT WORK. ADDRESSING SUCH ISSUES BY REFLECTING ON MEDIA, WHICH CHILDREN CAN STRONGLY RELATE TOO, CAN OFFER THEM A USEFUL ENTRY POINT TO UNDERSTANDING MORE COMPLEX ISSUES, WHILE AT THE SAME TIME INVITING THEM TO THINK DIFFERENTLY ABOUT SOMETHING AS FAMILIAR AS MEDIA TECHNOLOGIES. (IKE PICONE)

INFORMATION ABOUT THE ORGANIZATION THAT RUNS THE PROJECT

The Centro Zaffiria is a center for media education based in the municipality of Bellaria Igea Marina. Zaffiria offers and develops media education in schools, in collaboration with teachers, parents and children. The projects and workshops are carried out in close cooperation with the governing bodies of the schools throughout the territory. It’s the aim of Zaffiria to promote children’s rights and their social participation through the creative use of mass media. Zaffiria is financed by the province of Rimini, under the regional law of Emilia-Romagna on the right to study, and the municipality of Bellaria Igea Marina.

INITIATOR: Centro Zaffiria

PARTNER(S): Istituto Comprensivo di Pergola e San Lorenzo – Pesaro Urbino. With the supervision of Maria Arcà – CNR Roma (National Research Council, Rome)

CONTACT PERSON: Alessandra Falconi

CONTACT: Centro Zaffiria – Via Luzzatti 15 – Bellaria Igea Marina (RN), Italy

WEBSITE: http://www.zaffiria.it

PROJECT SUMMARY

Adolescents are intensive media consumers, but are often unaware of the financial dynamics behind products and media. Even media education tends to overlook this issue, perhaps because it is believed to be so far away from what boys and girls are interested in. The workshop’s challenge consisted in developing the students’ media analysis capabilities using financial aspects as tools to encourage them to think. Advergames, Facebook, YouTube, Wikipedia and video games were discussed and analyzed, using the issue of their free use as a discussion starter. How does a free service make money? What does ‘to profile users’ mean? What is digital identity?

AIMS: to help students to ask questions about what media they choose and how they use them; to strengthen their awareness of their online self; to develop curiosity about financial issues as they are relevant to us all in our everyday lives

TARGET GROUP(S): children aged 12

MEDIA: Internet, mobile phones

METHODS: active media work combined with the pedagogical Alberto Manzi method: educate to think. (http://www.centroalberto-manzi.it/englishversion.asp)

DURATION OF THE PROJECT: five days

RESOURCES NEEDED: approx. two people, plus the teachers at the school where the project takes place

DESCRIPTION OF THE PROJECT

The starting-point for Zaffiria was a school asking to work in greater detail on the various aspects of the economy that students have direct experience with, because they hear people talking about the economic crisis all the time. We needed to understand how much they knew; what connections they made between experiences and knowledge; what fears, concerns, expectations and conditioning this economic crisis led to. However, we needed the solution to be engaging, something that would allow the students to see for themselves that the economy is not just for experts but something that concerns each of our lives; even their lives as children.

The overall question the students have to work on is: How do sites such as YouTube and Facebook manage to be free? How do the people who work or have worked on these sites – developers, supporters, etc – get paid? Some of the answers at the beginning of the project were:

- The person who created Facebook is paid by all countries of the world.

- I think the owner of Google goes halves with the owner of Facebook.

- I think Facebook’s free because you pay for the dongle and Zuckerberg is rich because he gets money directly from the person who runs Internet.

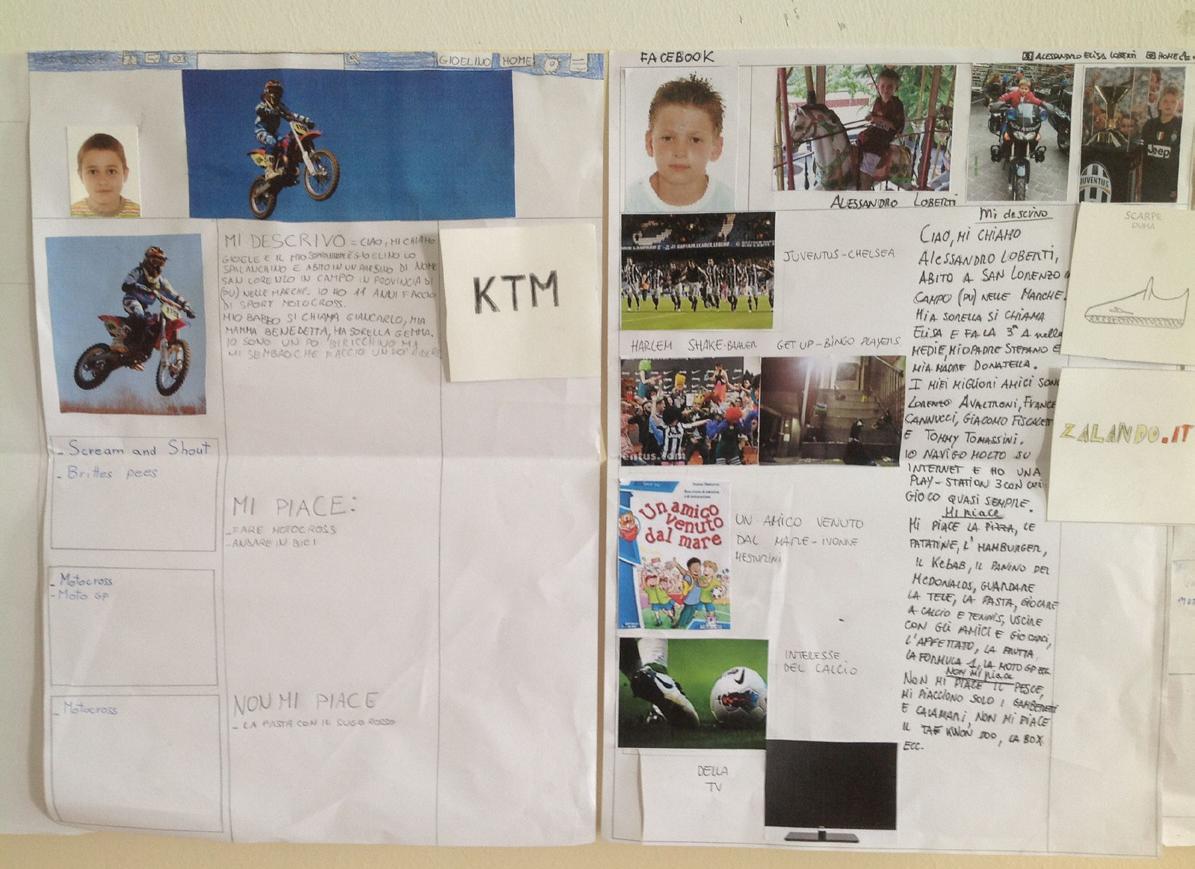

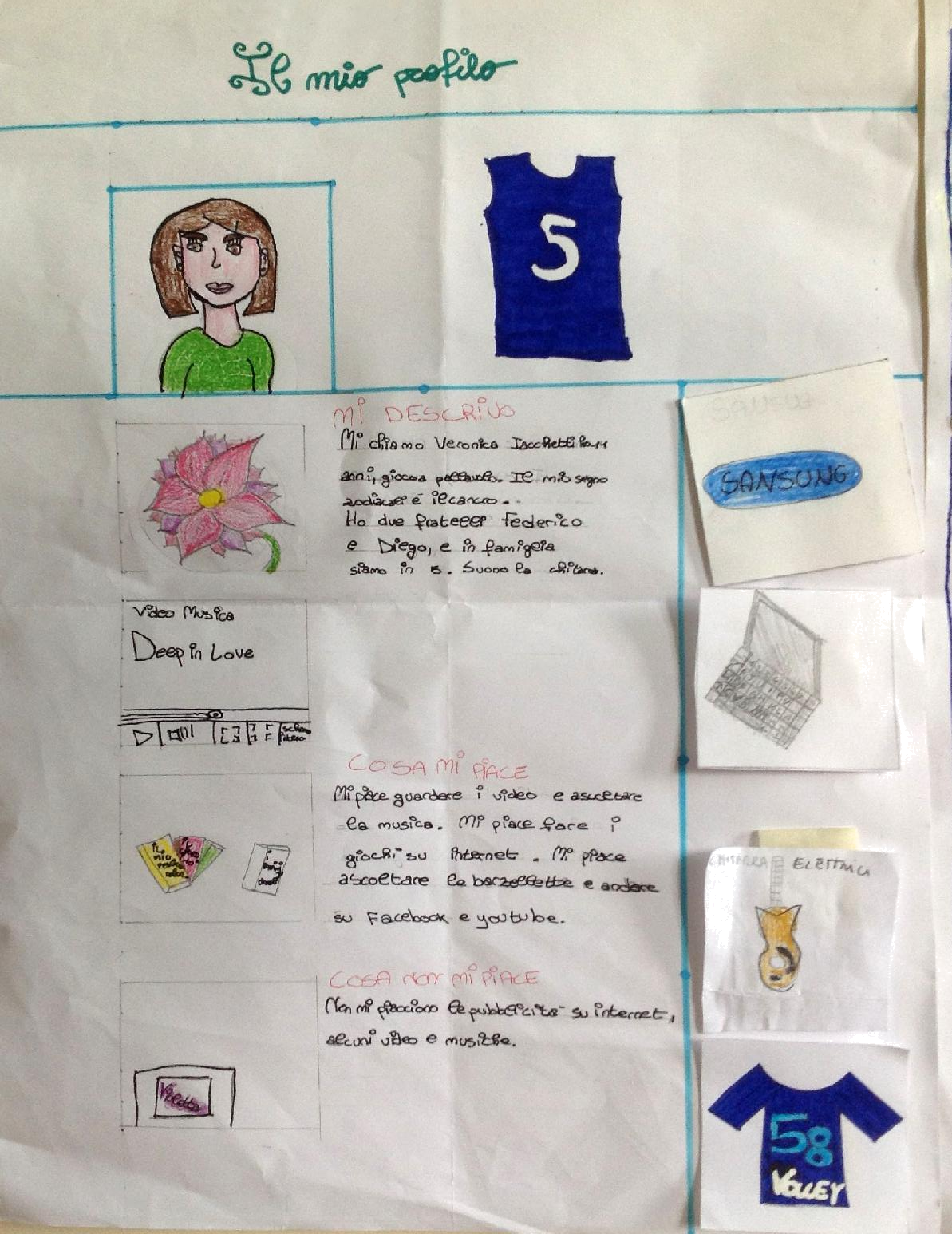

The children were asked to draw up their own profile, including what they love and don’t like, favorite books and videos, games and hobbies. They were also asked to see what adverts appeared on their Facebook profiles or when they were watching videos on YouTube. The aim was to make them look more carefully at the contents of their Facebook pages, especially the adverts that pop up, so that they could then discuss the connection between profile and advertising (each student prepared ads measuring 4 cm down each side, reproducing the advert that came up on their page).

How does a free service make money? What does ‘to profile users’ mean? What is digital identity?

A second objective was to pay more at-tention to how adolescents portray themselves; stopping to think about what they say about themselves and what they click on. The Facebook profiles were hung on the wall. To each profile the advert that the students estimated to be the most suitable was attached. They had to try to explain the reasons for their choices. What is it in the profile that indicates this person might be interested in a certain advert?

All children contributed to the discussion. The objective was to get them to think about how adverts don’t just pop up randomly, and how instead they are the product of carefully profiling. It seems that Facebook is a particularly good and understandable example.

Later in the project the discussion was extended to all online behavior. At that point Google, YouTube and video games were taken into consideration as well. The activity got the children to articulate the connection between the interests that emerge from a certain profile and the products that might match certain interests or tastes. What’s advertising got to do with the user’s profile?

METHOD(S)

The workshop was conducted by experimenting with the ‘educate to think’ method, which was suggested and implemented by a famous Italian teacher, Alberto Manzi. To educate students to think, we need to create a cognitive tension in them, a sense of curiosity that triggers research. Research is conducted through practical experiences and simulations; the objective is to ‘see’ better and in a nonobvious way. The group self-learns through the tangible experiences that the educator comes up with; they reassess their behavior, talking things through together to achieve shared knowledge, enriched by the experiences and knowledge of each individual.

The educator’s role is to take their knowledge to the next level by coming up with other experiences that serve to add to it, to help reshape and question it further, to complete it. Consequently, there is no wrong knowledge because the connections the child makes always have a sense (making sense to the child itself, at least) and this meaning, which is clearly expressed and put into words, contributes to the pursuit and building of knowledge.

ADDITIONAL DESCRIPTION OF ONE DAY OR PART OF THE PROJECT

WE ARE BARILLA

Judging from the discussions among the students, they still seemed to be somewhat uncertain as to what user profiling is. They came up with the following:

- Annoying users with meaningless advertising

- Violating privacy with outrageous advertising

- Engaging users in advertising

To help the students understand, they were asked to change their point of view, putting themselves in the shoes of the person who has to do the advertising. We performed a simulation: We’re the pasta giant Barilla and people have stopped buying our fusilli. We have to design a new Facebook page, but we realize it doesn’t look very exciting. We try to liven it up with a video game. This is where the work on advergames started: explaining what they are, how they work and why they work. Our analysis broadened to include many other Internet practices: playing video games, looking things up on Google and Wikipedia, watching videos, downloading applications… As the students told us what they already knew and talked about their experiences, the word ‘cookie’ came up and we talked about what it means, referring as much as possible to the students’ own activities.

We slowly got a better picture of the ‘net-work’ of practices that the children experience on their computers and mobile phones, and some connection opportunities also were shaping up (get more and more precise). We managed to grasp that our profile was laid out very accurately because we gave out a great deal of information about ourselves as we were navigating. With the students, we looked at the policy stated by Facebook regarding the issue of profiling and we read who the ‘partners’ of this major social network are; we analyzed what level of detail Facebook allows us to go into/promises us (by imagining that we have to promote a product).

Following a long journey, we’ve finally realized that to get something free, we end up giving out a lot of information about ourselves without even thinking that someone (outside our circle of friends) might be interested in it. Now, we hope, we can browse the Internet with a better understanding of the connections between the various platforms and with a better awareness of our digital identity.